The seminar series is open for anyone who wants to participate! If you are interested, please email cecilia.rosengren@lir.gu.se Zoom-link will be distributed a week in advance.

Spring 2026

Thursday 19 Mars, 16.00–17.00 CET

Björn Billing, Associate Professor History of Ideas and Science, University of Gothenburg

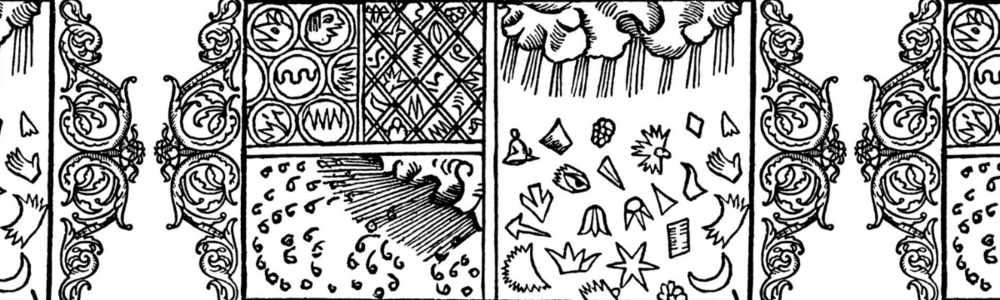

Visualising Icebergs: Early Modern Depictions, ca 1570–1770

Thursday 16 April, 16.00–17.00 CET

Maroesjka Verhagen, PhD Candidate History, University of Amsterdam

Preparing for Winter. Navigating Seasonality in Amsterdam's Early Modern Food Provision

Thursday 4 June, 16.00–17.00 CET

Wrapping up the research project Freezing cold. Reflections on results and how to move forward. We (Cecilia Sjöholm, Björn Billing, Cecilia Rosengren) invite everyone to join the discussion and our network for cold weather studies.

Autumn 2025

Torsdag 18 September, 16.00–17.00 CET

Digital release för K&K–Kultur og Klasse, Årg. 53, Nr. 139 (2025): KÖLD

https://tidsskrift.dk/kok/issue/view/12318

OBS! Seminariet äger rum på danska, norska och svenska.

Thursday 6 November, 16.00–17.00 CET

Trine Nordkvelle, PhD in Art History, Faculty of Humanities, University of Oslo and research fellow, Nasjonalmuseet, Oslo

True to Nature? Thomas Fearnley’s The Grindelwald Glacier (1838) between the real and the ideal

Thursday 11 December, 16.00–17.00 CET

Joana van de Löcht, Jun.- Prof, Dr, Germanistisches Institut, Universität Münster

How climate becomes text, how climate becomes literature. A theoretical approach

Spring 2025

Thursday 20 March, 16.00–17.00 CET

Chad Córdova, PhD, Assistant Professor of French, Cornell University

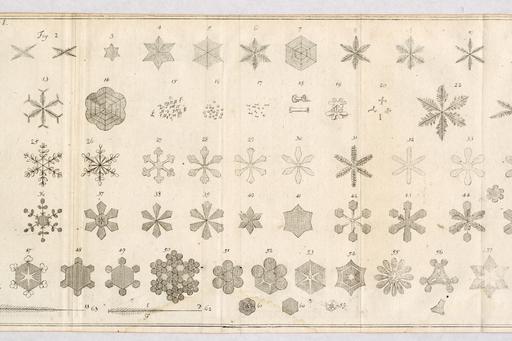

Descartes in Winter: Thinking in Smoke and Snow

Thursday 10 April, 16.00–17.00 CET

Rachel Kase, PhD, History of Art & Architecture, Boston University

The Little Ice Age and the Invention of Winter Landscape

Thursday 8 May, 16.00–17.00 CET

Stefan Norrgård, PhD, Researcher in historical climatology and climate history, Åbo Akademi

Climate and History. Ice Breakups in the Aura River in Turku, 1700-2000

Autumn 2024

Thursday 19 September, 16.00–17.00 CET

Dag Hedman, Professor emeritus, Comparative Literature, University of Gothenburg

Cold at the opera. Winds, ice and snow in early modern librettos

Thursday 24 October, 16.00–17.00 CET

Ellen Krefting, Professor, History of Ideas, University of Oslo

Currents of data: recording, modelling and visualizing cold, northern water masses in the 19th century

Thursday 21 November, 16.00–17.00 CET

Dominik Collet, Professor, Climate and Environmental History, University of Oslo

Narrating past climate. Socionatural entanglements in Little Ice Age Norway (1500-1800)

Spring 2024

Thursday 25 January, 16.00–17.00 CET

Christopher Heuer, Professor of Art and Architecture, The University of Rochester

'Treacherous Haunts': Olaus Magnus on Northern Undergrounds

Thursday 7 March, 16.00–17.00 CET

Robert W Rix, Associate Professor in English, Germanic and Romance studies, University of Copenhagen

The Arctic Sublime

Thursday 18 April, 16.00–17.00 CET

Reading seminar on two chapters from the collection of essays Le froid: Adaptation, production, effets, representations, eds Daniel Chartier, Jan Borm (2018) [A rough translation to English of the introduction in French will be distributed with the zoom link]

Thursday 9 May, 16.00–17.00 CET

Cecilia Rosengren, Associate Professor in History of Ideas and Science, University of Gothenburg

The Effects of Cold. Observations and representations in eighteenth century Sweden