- Home

- News and events

- Find news

- Scientists from all over the world come together as corals spawn

Scientists from all over the world come together as corals spawn

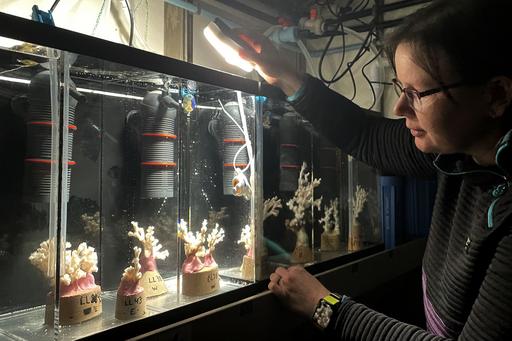

Right now, the corals are spawning in the aquariums at Tjärnö Marine Laboratory. Knowledge about coral reproduction is an important first step in the work to protect and preserve Sweden's only coral reef. Therefore, the researchers at the Department of Marine Sciences have been temporarily reinforced by coral researchers travelling from all over the world.

Inside the sturdy steel door there is a constant chill. The saltwater ripples through the aquariums on tables and shelves. It is pitch black. All to mimic a natural habitat for the white clumps of coral that glow behind the aquarium glass. But in recent weeks, the corals have had to put up with the researchers' eager and frequent slamming of the door.

"We are an amazing team all focusing on the spawning season – thirteen researchers and students from, among others, Chile, Mexico, USA and Belgium have gathered here at Tjärnö laboratory. We have got a lot of interesting data and my students have had great training for their further studies," says Rhian Waller, researcher in the Deep Sea and Coral Group at the Department of Marine Sciences.

Unique curve shows the viability of the reef

Rhian Waller´s research is about cold-water corals and sponges in deep seas all around the world. Now, she is working on the cold-water coral Lophelia pertusa. Unlike its tropical relatives, Lophelia builds reefs in dark and cold seas, sometimes down to depths of several thousand meters. In Sweden, the species is only found in northern Bohuslän, including Kosterhavet National Park, a short boat ride from Tjärnö Laboratory. Therefore, the station has become a vital center for Lophelia research.

Rhian Waller explains that the researchers have two focuses: to study eggs and sperm and various issues at the moment of fertilization, and to follow the further development of the fertilized eggs into small coral larvae and their various behaviours.

For her own part, Rhian Waller is particularly interested in developing a so-called fertilization curve. The curve shows the optimal concentration of sperm for successful fertilization - and has never been done before for any deep-sea coral!

"Such a curve is valuable for several reasons, for example understanding the viability of a coral reef. By knowing how much sperm is needed, we can see if males and females are close enough to each other, or if the distance is so great that the sperm may be diluted before reaching the eggs released by the females."

Inspection needed - around the clock

However, a fertilization curve is not something you draw up in a second. The practical work consists of mixing eggs and sperm in different proportions, and then examining how many eggs are fertilized and develop into embryos.

The first step is the hardest - to collect sperm and eggs from spawning corals. Then it is important to stand ready with the pipette to catch what is released. The researchers therefore have a schedule where they take turns to inspect the aquariums, sometimes once an hour around the clock.

"When we see a polyp getting ready, we check them every 15 minutes! And when sperm or eggs start to be released into the water, the alarm goes off and everyone comes running to help take care of everything. This can happen at any time, in the middle of the night or during lunch."

The deep sea is a challenging area for research, requiring big ships and sophisticated equipment. This may explain why so little is known about the biology of the Lophelia coral and other deep-sea species. Therefore, scientists are still dealing with very basic questions, such as are corals mono- or bi-sexual? Do they have internal or external fertilization? Do they reproduce once or several times a year? The difference is huge compared to what we know about tropical corals, according to Rhian Waller.

Essential for deep sea ecosystems

Rhian Waller also works with cold-water corals in the seas off Chile and in Alaska. There, the first attempts to get the corals to spawn in aquariums have just begun.

"Here, at Tjärnö Laboratory, research has come an amazingly long way; we know that we can produce larvae from Lophelia, and even carry out various experimental studies with them. For example, researchers in the group here are now even able to investigate how the larvae respond to various anthropogenic impacts."

Rhian Waller's interest in deep-sea corals stems from a fascination with their beauty and importance. She explains that Lophelia coral and other reef-building species are crucial to the deep-sea ecosystem. In an environment of vast sediment plains, the reefs create a three-dimensional habitat of cavities and nooks and crannies where fish, crustaceans and thousands of other sea creatures can live.

"If we want to preserve biodiversity in the deep sea, it is necessary to protect habitat-building species. But to do so, we need to understand how they function. Getting them to survive in aquariums, and then spawn and reproduce there, is an important first step."

Interview: Susanne Liljenström