- Home

- News and events

- Find news

- 3,500-year-old place of worship with mass burials discovered

3,500-year-old place of worship with mass burials discovered

As part of ongoing excavations in Cyprus, archaeologists from the University of Gothenburg have found mass graves and a large number of objects – evidence of the widespread trade carried in a Bronze Age city 3,500 years ago. The most sensational finds are a vessel which was used as a ritual object in funeral rites, a seal with cuneiform characters which is now being deciphered, and a scarab with hieroglyphics from the reign of Nefertiti.

The coronavirus pandemic has made it difficult to carry out archaeological digs abroad, but for a short period of time during the autumn of 2020, the opportunity opened up for the Swedish archaeological expedition in Cyprus, the Söderberg Expedition, to continue excavations in the large Bronze Age city of Hala Sultan Tekke.

“A large-scale magnetometer and radar survey carried out by us in 2017 indicated cavities below the surface in an area east of the city and it has been shown in previous investigations that these cavities are passages going to burial chambers,” says Peter Fischer, Professor in Archaeology who is leading the Swedish expedition along with Dr Teresa Bürge, both from the University of Gothenburg.

Left for future investigations

In the particular area where digs were done in 2020, there are three indications of the presence of graves from magnetometer detections:

“The first, whose excavation began in 2018, the second started this year, and a third is going to be left for future investigations. But there are hundreds more indications of tombs nearby.

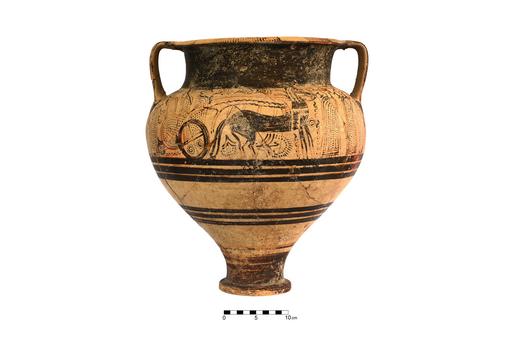

The first tomb has two chambers. The expedition has so far found 52 human skeletons and a large quantity of grave goods there. Among these are the only known complete vessel from Greece from around 1350 BCE with painted scenes of horse-drawn war chariots and people with swords.

DNA samples have been taken and strontium isotopes have been analysed. DNA analyses of the skeletons tell us about the origins and kinship of individuals, while strontium analysis of the teeth shows where they were born and where they moved to, for example, whether they were migrants or belonged to the local population.

“We have also taken bone samples for analysis in a synchrotron to find out about the environment during their lives through studying the accumulation of toxic substances in the bones of individuals,” says Peter Fischer.

Copper slag and parasites

Tonnes and tonnes of copper slag in the city have shown that there was large-scale production of copper, and this exposed the people to substances that are harmful to human health such as lead and arsenic, which are common in copper ore.

Analyses of soil samples in the region around the skeletons’ abdomens also indicate that they suffered from parasites during their lifetime. The mortality rate among children and young people was very high and a person aged around 40 was among of the oldest.

The second tomb excavated in 2020 turned out to contain hundreds of finds, many of which were imported from areas corresponding to today’s Greece, Crete, Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Palestine and Egypt.

Unique ceramic vessel

The nature of the new structure that archaeologists began to excavate this year is very different from the former tomb.

“It consists of an underground dome, coated on the inside with a thick layer of a plaster-like substance which stabilises the construction. The space could be accessed via a passage from the surface.

Among the ceramics there was a roughly 40 cm tall vessel used as a ritual object in funeral rites.

“It’s unique and we are in the process of restoring it. A similar vessel has not been found anywhere else. It is covered in intricate patterns painted in a red-brown colour. In addition, it is embellished with applications of large rings and the head of a ram,” says Peter Fischer.

The material indicates that the vessel was imported from Greece around 1350 BCE.

“In view of this ritual object being found and the large quantity of finds not associated with the skeletons, this structure must be explained as something more than just a large tomb. Our interpretation is that we have exposed a place of worship where rites in connection with death were practised.

Seal with cuneiform characters

Both structures were used for a couple of hundred years, from about 1500 to 1300 BCE. This means that for each rite/burial, they were opened and then sealed again with earth.

“A rough estimate is that in the first tomb with 52 skeletons there are 10 generations. They belonged to the members of a very wealthy family, probably of the ruling class in the city. But one or two layers of burials remain.

In addition to the large quantities of fine ceramics, there were some unique finds of other materials. Foremost among these was a seal made of haematite, a shimmering greyish-black stone, from the oldest Babylonian Empire (now Iraq). This seal, dated to between 1800 and 1600 BCE, has sophisticated engravings of gods, humans and animals. This means that the seal was used for about 300 years before it ended up in Hala Sultan Tekke.”

“In addition, which is the most sensational, there are three lines of cuneiform characters, making it the most important find here in archaeological circles. You can read the name of a king for example, and we are currently looking for that king in various cuneiform archives from Mesopotamia, which will give us a more accurate date and perhaps an explanation for how the seal ended up in Cyprus, 1200 kms away.”

Large number of finds

Among other finds are an Egyptian lotus-shaped gold ornament inlaid with precious stones and faience (tin-glazed ceramic), as well as a number of other pieces of jewellery in silver, bronze and gold.

“Another find from Egypt is a scarab with an inscription in hieroglyphics that has been deciphered as: “All well. All live” – a greeting from the reign of Nefertiti and her husband Echnaton from about 1350 BCE. We also found two large female figurines with bird faces and clearly marked genitalia. Each figurine has four earrings.

The new finds in the ancient city reflect the key role that Cyprus and in particular Hala Sultan Tekke played as a trade metropolis in the Mediterranean economic system. The city’s wealth was based on exports of copper and purple fabrics.

There are unmistakeable cultural and economic links between the city and a large geographical area. The findings come from Sardinia in the west to Afghanistan in the east 5,000 km away, and from Turkey in the north to Egypt in the south,” says Peter Fischer.

Trade metropolis for 500 years

Exotic ceramics were imported into to the city from Sardinia and from Turkey, and from the Levant there are metre-high transport vessels which were filled with wine, oil and grains. Luxury goods made of precious metals and stones came from Egypt and the seal found in the dig is proof of contact with the Middle East. There are also imports from Afghanistan in the form of lapis lazuli, a deep blue stone that is found in pieces of gold jewellery from this time.

The ancient city spanning approximately 50 hectares lies on the shore of Larnaca’s salt lake, close to the airport, which was the city’s harbour during the Bronze Age. Later, isostatic uplift separated the port from the sea and may have contributed to the abandonment of the city around 1150 BCE.

“The protected situation of the harbour helped Hala Sultan Tekke to become a trade metropolis for 500 years, with long-distance contacts evident from the very abundant find material,” says Peter Fischer. War and climate change combined with isostatic uplift contributed to the demise of the city,” says Peter Fischer.

The field work was mainly sponsored by the Torsten Söderberg Foundation (Swedish id. ÖT4/18). Additional research was supported by the Royal Swedish Academy of History and Antiquities in Stockholm (Swedish id. FS2019-0100), The Royal Society of Arts and Sciences in Gothenburg (2020), The Swedish Research Council (Swedish id. 2015-01192), and INSTAP (USA id. 0000000060).

Contact details:

Peter Fischer, phone: +46(0)707-53 43 17, e-mail: peter@fischerarchaeology.se

Text: Johanna Hillgren