Protocols of Killings: 1965, distance, and the ethics of future warfare

Short description

This project probes the connection between violence, distance and accountability, by drawing aesthetic parallels between the protocols surrounding the Indonesian 1965-66 massacres and the drone warfare’s technologies of the future.

Both the Indonesian 1965-66 massacres and drone warfare are hyperdistant killings – the 1965 massacres were abetted and condoned by leading democracies of the world – and both are full of secrecy. However, a large archive about the Indonesian mass killings 1965-66 was finally declassified in 2018. This 30,000-page archive comprises daily inter-embassies communication from the U.S. Embassy in Jakarta between 1964-68, surrounding the killings.

The project will aesthetically translate patterns of group dynamics from this archive into participatory performances that I will workshop with different publics around the world, engaging survivors groups as facilitators. Participants will discuss embodied experiences from the workshop to understand how distance links with accountability when it comes to violence. The protocols that shape the group dynamics from the Indonesian U.S. archive may be similar to the decentralised protocols of the autonomous swarm drone that operates as a pack without a central control, a technological feature of future warfare.

State of the field

The state-of-the-art of drone warfare is not separable from public anxiety. A root cause of this anxiety is secrecy, the non-transparency of the drone strikes, which causes uncertainty and fear. In 2019, anxiety was heightened after a drone strike of an oil processing facilities in Saudi Arabia that cut the country’s oil production by half. The attack was later claimed by the Yemeni Houthi rebels – not even an official government body. This serves as a glimpse to the other root cause of anxiety: the potentially uncurbed global burgeoning of this “killing from a distance,” which – as Dave Grossman’s 1996 research had shown – makes killings as easy as playing a video game.

Secrecy

A subversive artistic strategy often applied in drone art is to “make visible the invisible” (Danchev, 2016). In response to secrecy, for example, artist Trevor Paglen shows photographs of secret military bases taken from a publicly accessible location (2012), and artist James Bridle draws 1:1 chalk outlines of drones – similar to chalk outlines we see in crime scenes – to bring the physical presence of a drone into public eye (2012). Here secrecy is also connected to absence, which political scientist Oliver Kearns describes as the rumours and debris left in the lacuna, and which forms public’s perception, after a covert strike (2017). The research group Forensic Architecture (2013) gathers evidence from various sources to reconstruct spatial and material presence that was destroyed in drone strikes, to present how the strike might have unfolded. So, to make visible the invisible, they fill in presence in the absence.

Yet, in his discussion of absence, Kearns problematises this impulse of filling-in presence in the absence. He suggests an ethical risk of this act merely reiterating the struggle to comprehend, which takes away the public’s attention from the facts of the violence itself, a violence that is already wholly present in the absence. I recognise a resonance of this especially through my own work on the Indonesian mass killings 1965-66 (henceforth 1965), where one of the most typical arguments would end in a disheartened admission of defeat by this struggle to comprehend (e.g. comments in the Instagram outlet of 1965 Setiap Hari, 2019), resulting in apathy (“let’s stop arguing about this and move on, we will never know the truth anyway”). Kearns compellingly argues that a more ethical response would be to acknowledge the political dynamics of absence as it is, and resist the impulse to fill in, because it is precisely the absence that shapes the significance of the violence. Proponents of acknowledging – instead of filling in – presence in the absence may also concur with the opinion that making visible the invisible risks being a reproduction of the violence. The long debate about war photography is illustrative of this risk. In drone warfare, this reproduction of violence could be true as well in responses to distance.

Accountability

Some artists show the victims and their lives, something the public also rarely see. A Pakistani collective’s work shows a giant photographic reproduction of a girl who lost her family in a drone attack, #NotABugSplat, so that the drone operators who happen to aim would be seeing her image from the sky (Joslin et al, 2014). Photo journalist Noor Behram (Shah and Beaumont, 2011) documents drone strikes since 2004 in his home region Waziristan, a mountainous area in Pakistan. These photographs, not for the faint of hearts, have also been shown publicly in the U.S., where the drone strikes originated. All these strategies of subversion apparently operate on the assumption that distance makes killing easier because the killers cannot see the victims. Therefore, to have the killers see the victims – or in other words, to have this distance overcome – would inspire penitence. This is also true for the shepherd Gyges in Plato’s allegory, as philosopher John Kaag and international relations scholar Sarah Kreps discusses (2014), where making visible the invisible is the ethical logic of the circumstances. Gyges chanced upon a ring that can make him invisible, which allowed him to kill without anyone seeing. Because no one can see him kill, he would not get convicted. What is always implied in issues of secrecy and invisibility is the notion of ethics and accountability: we make visible the invisible in order for them to be accountable.

Giving the victims presence through overcoming distance is also like giving voice to these victims, as in court proceedings when victims represent themselves to testify, to prove a crime that has been done to them. However – to return to and complicate Kearns’s argument – how can we acknowledge the political dynamics of absence without being complicit, when it is exactly the narrative of non-presence, or of other-presence that the State upholds? When a site is made absence, it becomes a contested site. In Indonesia's case, this absence was immediately filled in with fabrication of memory that replaces the absence. It is difficult to imagine the State pausing in their action to reflect on the ethical implications of it. Diyah Rachmi Larasati (2013) rigorously chronicles this State’s filling in presence to replace absence, through her own position as dance scholar as well as an idealised state-sanctioned dancer that was recreated to replace the murdered, disappeared, historical dancing bodies (of which her family was also part) in Indonesia. The logic of invisibility can also be reversed: if you fear to be visible, perhaps you are in the wrong. To further illustrate the binary inversion of invisibility, absence and accountability of the State: in the International People’s Tribunal held for 1965 in 2015, 50 years after the so-called crime against humanity, almost half the witnesses testified with a pseudonym and behind a black curtain, and it was due to safety consideration that the tribunal was held out of Indonesia (Narrative Report of the IPT 1965, 2017). The fact that none of the governments indicted as complicit responded to the tribunal is illustrative of the tendency in the transitional justice field – and true as well in art – where more significance is increasingly placed in accounting for the past, or providing an account, rather than to hold perpetrators accountable (Ainley, 2011, p. 424).

Distance

While secrecy teases out clear-cut binary reasonings in many cases, distance is in comparison puzzling. Both for the State that creates the secrecy, and the public that struggle to comprehend the secrecy, distance is a common problem. It looks like, however small, distance will never be overcome. The 2015 Drone Papers, for example, refer to a "tyranny of distance" in Yemen and Somalia, where the geographic distance between the bases and the targets of the drones is on average 450 kilometres in Yemen and 1000 kilometres in Somalia. These, according to the leaked documents, make attacks challenging. This so-called “tyranny of distance” in drone warfare makes it sound like it is still dependent on geography and geology, just like any traditional war since Sun Tzu’s The Art of War. This is curious, because one would think that 450 kilometres and 1000 kilometres should be no heavy matter for drones, a supposedly advanced technological machine. Apparently, war has not changed despite the seemingly impenetrable technologies.

What had somewhat become a side narrative of distance is elaborated in Caroline Holmqvist’s (2013) discussion on the ontologies of war (with human as a central inquiry). I describe this as a side narrative because it is often disregarded in discussions of killing from a distance – that distance, and killing from a distance, are not as simple as imagined. Holmqvist problematises amongst others the idea that distance makes killings easy, calling the video game argument “simplistic,” for it is exactly the immersive virtual reality of the video game-like system –with screens that draws you in – that makes it effective as a tool for military training. Following Holmqvist’s materiality approach, an operator’s screen indeed draws in the operator more than it draws in the public, simply because of distance. So, what the public cannot see, the operator can see clearly. As the drone operator interviewed in Omer Fest’s 5,000 Feet is the Best (2011) also recounts, it turns out that “distance killing made easy” has been contested by the growing evidence that even operators of drone strikes suffer from PTSD because of the killings. Joshua Oppenheimer’s film that features the murderers of 1965 – operators, as I will argue in the next section – also depicts this: their pride in having killed for the State that deems them heroes is jumbled with endless undigestible, convoluted remorse (2012). But – within the distance between the operators and the central decision-maker – where should remorse be felt?

To go back to drone operators: in turn, the screen, smaller in distance to the operator, can also see the operator clearly. While the public fears that drones will allow the military to kill as they like because the public cannot see them, there is actually a growing concern within the military that this new technology means that their every single move can and will be recorded closely to be made accountable (Singer, 2009, pp. 390-1).

Variants of distance

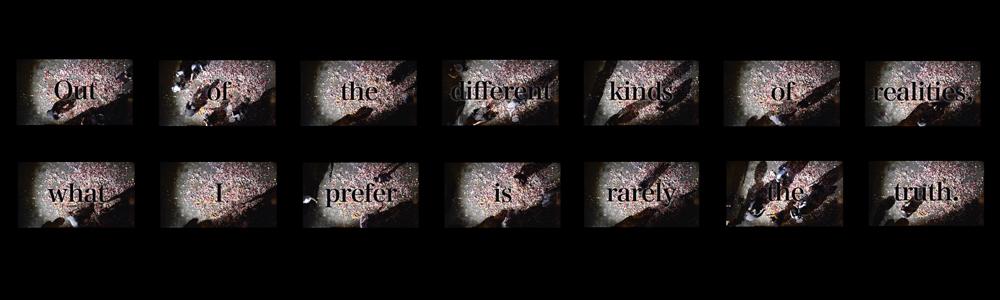

Through my work on 1965 since early 2000s, I learned how secrecy, distance and accountability can be intimately entangled. The first kind of distance I found is always entangled in secrecy. Their attachment owes to the fact that this distance is produced by secrecy. This distance is temporal, and it will grow as long as secrecy is in its roots. As this temporal distance grows, accountability lessens. Like a colour photograph that fades with the growing of this temporal distance, some components of the reality also fade (McGovern-Basa, interview with Wulia, 2017).

There are other kinds of distance, with different relations to secrecy and accountability. In this section, for example, we have so far been discussing distance in a strictly spatial sense. After all, spatial distance is what the understanding of “killing from a distance” is at present: it is some kind of a remote control killing, a killing made from behind the screen, from a geographical location far away from the killing field. This distance is not always entangled with secrecy, although within Bush, Obama and Trump’s presidency it is.

The third kind of distance is probably the most complex, and one that will need to be substantially addressed in this research. Perhaps I can describe it as ‘protocological’ distance, to align with Galloway’s protocological technologies (2004), as it is related to procedures and bureaucracy, of which the case of Eichmann in Jerusalem as accounted by Hannah Arendt can provide directions. This distance is perhaps not intended to entangle secrecy, but by its nature, some parts are impenetrable. However, unentangling distance in this context promises a hint into accountability and responsibility.

The public

Identifying an interest in materiality within security studies, William Walters (2014) brings in Bruno Latour’s dingpolitik, noting how things are made public in recent scholarship. The public is omnipresent in all these discussions on drone warfare, but it is never clarified in these constellations what the public do other than to be given information to see. This brings resonance to Walter Lippman’s phantom public. While I do acknowledge that all the scholars and artists are also part of the public, there seems to be an audience that we speak to, which becomes the recipient, but is never truly accountable either. In my project I will ask if they can be other than a passive recipient. Looking at warfare as embodied performance, I will engage the public in a kind of an embodied forum. This forum will be seen as a cultural forum rather than a judicial governance, as the embodied experience will be injected through culture rather than governance.

References

Ainley, K. (2011). Excesses of Responsibility: The Limits of Law and the Possibilities of Politics. Ethics & International Affairs, 25(4), 407–431.

Arendt, H. (1994). Eichmann in Jerusalem. New York: Penguin.

Danchev, A. (2016). Bug splat: The art of the drone. International Affairs, 92(3), 703-713.

Dirgantoro, W., Hutabarat, E., Johani, M., Mayda, A., Moechtar, K., Mohan, F., Purbaya, R., Setiawan, K., Stevy, S. F., Wulia, T. (2015-). 1965 Setiap Hari [collection and dissemination in various forms of personal histories related to 1965-66 Indonesian mass killings]. Various outlets.

Forensic Architecture. (2013, April 16). Drone Strike in Mir Ali. Retrieved March 1, 2020, from https://forensic-architecture.org/investigation/drone-strike-in-mir-ali

Galloway, A. (2004). Protocol: how control exists after decentralization. Cambridge: MIT.

Grossman, D. (1996). On killing: the psychological cost of learning to kill in war and society. Boston: Little, Brown.

Holmqvist, C. (2013). Undoing War: War Ontologies and the Materiality of Drone Warfare. Millennium: Journal of International Studies, 41(3), 535–552.

Joslin, J. A., Bob, Sallu, RichP, Nabeel, Frybulous, J., … Cognitive Humanity Project. (2014). #NotABugSplat. Retrieved March 1, 2020, from https://notabugsplat.com/

Kaag, J. J., & Kreps, S. E. (2014). Drone Warfare. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Kearns, O. (2017). Secrecy and absence in the residue of covert drone strikes. Political Geography, 57, 13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2016.11.005

Larasati, R. D. (2013). The dance that makes you vanish: cultural reconstruction in postgenocide Indonesia. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

McGovern-Basa, E. (2017). Tintin Wulia: Not Alone. Art Asia Pacific, (103), 108–117.

Paglen, T. (2012). Limit Telephotography. Retrieved March 1, 2020, from http://www.paglen.com/?l=work&s=limit

Shah, S., & Beaumont, P. (2011, July 17). US drone strikes in Pakistan claiming many civilian victims, says campaigner. Retrieved March 9, 2020, from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/jul/17/us-drone-strikes-pakistan-waziristan

Singer, P. W. (2009). Wired for war: the robotics revolution and conflict in the twenty-first century. New York: Penguin Books.

Walters, W. (2014). Drone strikes, dingpolitik and beyond: Furthering the debate on materiality and security. Security Dialogue, 45(2), 101–118.