- Home

- News and events

- Find news

- SEK 10M awarded for study advancing cell therapy

SEK 10M awarded for study advancing cell therapy

An automated system for mass-producing targeted white blood cells, with one billion T cells injected into liver tumors. Lars Ny and his research team secured a SEK 10 million grant from the Swedish Cancer Society, advancing cell therapy to new heights.

T lymphocytes, or T cells, play a pivotal role in the body’s immune system. These adaptive white blood cells can tailor their responses to specific threats, such as viruses or cancer cells.

Lars Ny, Professor of Immuno-oncology at the Institute of Clinical Sciences, is leading a study where cancer patients receive a novel cell therapy developed by researchers at the University of Gothenburg. The study targets the local treatment of secondary tumors (metastases) in the livers of patients with ocular melanoma.

Broad collaboration

“To receive such a substantial grant is incredible. Competition for funding in clinical treatment studies is exceptionally tough. The fact that we secured it indicates that the Swedish Cancer Society recognizes our expertise and the high quality of our work,” says Lars Ny.

“Ocular melanoma is rare, but researching it is crucial. Currently, there are no effective treatments that significantly impact survival once the disease has spread. Thanks to the grant, we have the freedom to conduct this study comprehensively. We can delve into analysis more profoundly than we could otherwise. We have the resources to engage all the necessary experts in our group. This fundamentally alters the conditions for implementing an advanced and innovative approach.”

The research project involves not only oncologists.

“We collaborate with various experts, including radiologists, surgeons, tumor biologists, and immunologists. This multidisciplinary teamwork is the key to success.”

A thousand cells become a billion

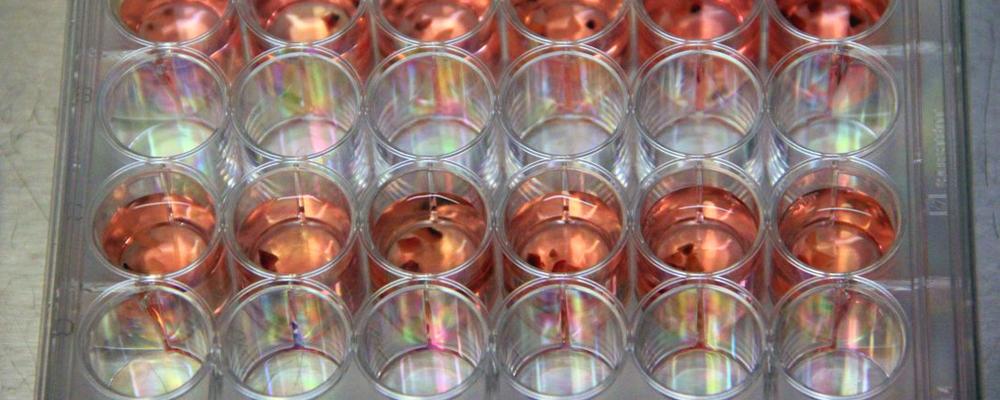

The study, conducted on six patients, aims to develop and evaluate a method for automated production of endogenous T cells (tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, TILs), which are then injected into the tumor.

The process takes place in four steps:

- A piece of the tumor is removed, and a few thousand T cells are isolated.

- Manual cultivation for two weeks increases the T cell count to about one million.

- Over the next two weeks, a machine automatically produces T cells, bringing the count to at least one billion.

- Through a catheter inserted into the groin artery, a large number of T cells are injected directly into the tumor tissue in the liver.

Challenges with the method

What are the difficulties with this new method of cell therapy?

“Firstly, we need to manufacture the T cells according to all the established standards and meet the requirements of the Swedish Medical Products Agency. Also, ensuring the cells maintain their activity and remain free from contamination by bacteria or viruses is crucial,” says Lars Ny.

What are the potential risks for the patients involved in the study?

“The primary goal of the study is to confirm the safety of the treatment. When we introduce such a large number of cells into a small tissue area, there is a theoretical risk of bleeding and clots in the liver. However, in the initial treatments on the first patients, we haven't observed anything of this nature.”

Competing immune cells

Other immune cells compete with the supplied T cells. It is crucial to fight these immune cells to prevent an inappropriate immune reaction in the body. This is partially prevented by patients receiving chemotherapy before the procedure.

“An essential aspect of this phase 1 study is gaining insights into how to design the subsequent clinical treatment study,” says Lars Ny.

If the study shows that the cell therapy has a good effect against metastases in the liver in patients with ocular melanoma, he envisions expanded possibilities in the future.

“This form of cell therapy might also prove relevant in other cancer types that spread to the liver, like skin melanoma and cancers of the colon or pancreas.”

Text: Jakob Lundberg