The Albatross Expedition

The Swedish scientific Albatross Expedition sailed around the world in 1947 - 1948. This pioneering expedition made invaluable contributions to our knowledge about the ocean and laid the foundation for today's modern deep-sea research. The methods and measuring instruments developed on board the Albatross are still in use today, and the results of the expedition have had a huge impact on oceanographers, marine geologists, and climate scientists all over the world.

The Albatross Expedition was a Swedish deep-sea expedition that sailed around the world between 4 July 1947 and 3 October 1948. The initiator and expedition leader of this pioneering oceanographic expedition was Hans Pettersson, Professor of Oceanography at the University of Gothenburg.

When the expedition returned to Gothenburg, the ship was loaded with record-length sediment cores, newly developed sampling instruments, and countless deep-sea organisms from 400 sampling stations in the Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, and Indian Ocean.

The Albatross expedition thus laid the foundation for an entirely new understanding of the deep sea, sediments, oceans’ history, and climate.

The Kullenberg Piston Corer - a Swedish invention

It was because of a Swedish invention that the Albatross expedition became so successful.

During the expedition, the scientists used the Kullenberg piston corer – a newly designed Swedish sediment sampling instrument. The inventor of the piston corer was Börje Kullenberg, who developed the pioneering mechanisms of the corer together with instrument maker Axel Jonasson in Gullmarsfjorden during the 1930s and 1940s.

The sampling instruments previously used to retrieve sediments from the ocean floor had only managed to go down about 2 metres into the sediments, i.e. a few thousand years.

With the help of the Kullenberg piston corer, the Swedish researchers managed to retrieve sediment cores as long as 20 metres – which made an additional 2 million years!

Today it’s standard method to use the Kullenberg piston corer for collecting samples of soft sediments, and it’s now possible to take sediment cores up to more than 60 metres with a Kullenberg corer.

The mechanics behind the Kullenberg piston corer

The Kullenberg invention is also simply called a “piston corer”.

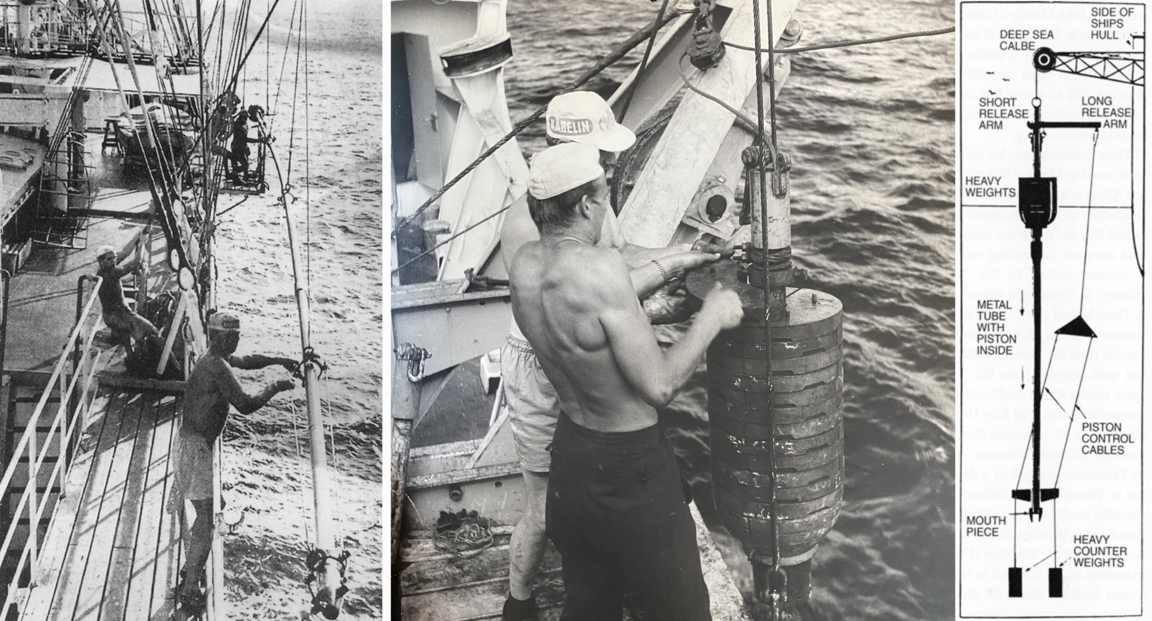

The Kullenberg piston corer is constructed as a long metal tube with heavy weights on top.

Inside the metal tube, there is a plastic tube. The tubes are lowered together into the water and just before they reach the ocean floor, a mechanism is triggered that makes the tubes, with the help of the heavy weights, to fall freely into the sediment.

The resulting negative pressure draws sediment up from the ocean floor into the plastic tube, forming a so-called “drill core” or “sediment core”.

Ground-breaking scientific discoveries

Start of new discipline: palaeoceanography

Thanks to the record length sediment cores from the Kullenberg corer, containing deep-sea clay going back 2 million years, scientists were able to, like archaeologists, study historical climate and ocean processes in the sediment layers.

For example, the scientists were able to see historical changes in the climate, and discovered that the last 2 million years have been characterised by more ice ages than previously believed.

The Albatross Expedition's long sediment cores thus marked the beginning of a new scientific discipline, palaeoceanography: “the study of the oceanographic history of the Earth through the analysis of ocean sedimentary deposits”.

Since then, several scientific disciplines have developed, including marine micropaleontology, physical palaeoceanography, and palaeoclimatology.

The discovery of oxygen isotopes as climate informer

It was also in the samples of deep-sea clay brought back by the Albatross Expedition that scientists first discovered that oxygen isotopes in marine microfossils act as a “palaeo-thermometers”, and can provide information about the climate of the past.

Microfossils, such as the amoeba-like organism foraminifera, are preserved in different layers of sediments. Foraminifera form their shells partly from limestone, and in the limestone shells scientists can measure oxygen isotopes that provide information about temperature and salinity, for example.

Oxygen isotopes are now known as the “backbone of palaeoceanography”. It’s a method that, for example, marine geologists and climate scientists around the world still use in their work today.

Contribution to Marine Biology

The Albatross expedition also brought new information to the field of marine biology. Before the expedition, the prevailing view among the world's scientists was that life could not exist at great ocean depths.

But the expedition trawled the record depth of 7 900 metres, and the trawl catch contained both large and small organisms. This allowed the Swedish researchers to prove that marine life existed even at such great depths.

The Expedition's arduous journey

The route along the equator

The Albatross Expedition's route was mainly located inside the Tropics, along the equator. This was to ensure the best possible weather conditions throughout the expedition. Nevertheless, winds and storms could be strong, especially in the Indian Ocean.

Albatross left Gothenburg on 4 July 1947 and travelled through the English Channel, down the North Atlantic through the Panama Canal to Tahiti, Hawaii, New Guinea, and Bali in the Pacific Ocean. The expedition then travelled across the Indian Ocean via Sri Lanka and the Seychelles, through the Red Sea and the Suez Canal to the Mediterranean. They then crisscrossed in the Atlantic again before arriving in Gothenburg on 3 October 1948.

All 400 measuring stations are marked on the map in numerical order.

Life on board

We now know a lot about the voyage, and life on board, because Hans Pettersson wrote a journal and sent the pages home to his wife Dagmar Pettersson during the expedition. The pages are today stored in the Manuscript Collections at the University Library in Gothenburg.

Life on board was sometimes hard in the intense heat and sunshine: poor sleep, insect bites, cockroaches, and heat rashes plagued the crew.

But there was not only heavy research work on board, the expedition also met with inhabitants and governors of the islands the expedition visited for supplies, such as Hawaii, Bali, Tahiti, and the Seychelles.

From Hans Pettersson’s journal:

Panama-Galapagos 29 August 1947

"Out of overcast splendid sunshine but not too hot. Breeze and slight swell from the SW. Corer not ready b c o yesterday's trawling. First into the sea at lunch up at 3 o'clock from 3000 m, 11 metre pipe dark green mud on the outside. Completely filled without gaps."

Papeete-Moorea 29/10 1947

"Up at 6 a.m. woke up R and gave him sardines at my place Ashore at 7.30 a.m. was shaved and left in Donald's motorboat for Moorea. /.../ Beautiful island Huge volcanic cones that push up to 4000. one of them with a hole through the top. /.../ Ordered lunch in a small beach hotel and while waiting took a walk and bathed in the warm but intensely salty ocean water."

Translation to English: Annika Wall

Some anecdotes from the expedition:

- Three from the crew escaped in Honolulu, Hawaii. Thereafter, there were strict restrictions on the crew.

- Gustaf Arrhenius received a telegram in Port Victoria, Seychelles, that his fiancée was tired of waiting and wanted to break their engagement, so he went home and got married. Then he returned to the expedition again after the honeymoon.

- The expedition also ran out of money when they arrived at the Red Sea. Hans Pettersson then travelled home to ask for additional funding. The Expedition was thus able to make the final legs in the North Atlantic.

Albatross - a converted school ship

The vessel used on the expedition was the Broström Group's school ship Albatross, a 4-masted motorised sailing vessel sailed by the Group's naval students.

The ship was rebuilt for the Expedition with laboratories, space for the long winch, and storage of all the expedition's samples. There were single cabins for the scientific staff, but it was not as comfortable for the students.

The people behind the Expedition

A total of 44 people travelled on the Albatross. The scientific working group consisted of 14 people, including:

- Hans Pettersson, Professor of Oceanography at the University of Gothenburg.

- Börje Kullenberg, later Professor of Oceanography at the University of Gothenburg.

- Axel Jonasson, instrument maker who worked with the Kullenberg piston corer.

- Nils Jerlov, later Associate Professor of Oceanography at the University of Gothenburg.

- Fritz Koczy, later Professor of Oceanography at the University of Miami.

- Gustaf Arrhenius, later Professor of Oceanography at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego.

- Waloddi Weibull, Professor at KTH Royal Institute of Technology.

- John Eriksson, medical doctor.

There were also another 30 crew members on board, with a variety of occupations such as:

- commander

- mate

- engineer

- able seaman

- apprentice seaman

- carpenter

- steward

Hans Pettersson, Professor of Oceanography at the University of Gothenburg

Hans Pettersson was Sweden's first professor of oceanography and founded the Oceanographic Institute in 1938, later a department at the University of Gothenburg.

It’s because of Hans Pettersson that the expedition took place at all, through his enthusiasm and ability to convince financiers to fund the expedition. The Broström Group lent the ship Albatross and its apprentices to the expedition nearly free of charge. Some of the financiers included manufacturer Gustaf Werner.

Hans Pettersson wanted to travel in the footsteps of the Challenger expedition and map the ocean floor using various technical measuring instruments. At the time, there was little information about the deep sea, and Hans Pettersson wanted to be the first to discover new records.

Börje Kullenberg, later Professor of Oceanography at the University of Gothenburg.

Börje Kullenberg obtained his PhD in Lund in the field of physics, but later came to focus on oceanography.

Early on, Börje Kullenberg was interested in solving the problem of retrieving complete and undisturbed sediment cores from the ocean floor.

Börje Kullenberg was the mastermind behind the setup of the Kullenberg piston corer. Together with instrument maker Axel Jonasson, he then developed the mechanisms of the corer.

The piston corer was developed and tested over many years prior to the Albatross expedition, including at the Bornö hydrographic station in the Gullmarsfjord, and on expeditions in the Mediterranean.

Summary: Scientific progress thanks to the Expedition

Scientific progress thanks to the Albatross Expedition:

- Development of a new scientific discipline: palaeoceanography. That is, the study of the oceanographic history of the Earth through the analysis of oceanic sedimentary deposits.

- Using oxygen isotopes to extract climate information from calcareous microfossils such as foraminifera.

- Marine life in the deep sea. Before the expedition, the prevailing view was that life could not exist at great ocean depths.

Technological advances thanks to the Albatross Expedition:

- The Kullenberg piston corer, invented by Börje Kullenberg. Today, the use of the piston corer is an accepted method, and it is now possible to retrieve sediment cores of more than 60 metres in length with a piston corer.

- Seismic exploration methods to record the thickness of sediment layers, developed by Waloddi Weibull, professor at KTH.

The samples' importance for modern science

The Albatross samples is not just a collection — it is an irreplaceable scientific archive of global relevance. The contrast between these untouched samples and today’s profoundly altered marine environment makes the Albatross archive a cornerstone for understanding long-term human impacts on the ocean.

Most crucially, the material was collected before atmospheric nuclear testing began, which irreversibly altered global carbon-14 levels. This makes the Albatross samples one of the few remaining untainted baselines for:

- Benchmarking pre-bomb ¹⁴C levels, essential for accurate radiocarbon dating

- Studying natural carbon cycling and distinguishing fossil-fuel emissions

- Calibrating Earth system models used in climate prediction

- Reconstructing baseline ocean and climate conditions with unprecedented clarity

- Providing an early reference point for the onset and spread of anthropogenic pollutants, including microplastics, now increasingly detected in sedimentary records worldwide

This collection also serves as a rare environmental benchmark taken just before the 'Great Acceleration' — the post-World War II period that saw an unprecedented surge in human impact on the Earth system. Since the time of the Albatross expedition:

- Global industrial production has increased by over 1,000%, and

- Seaborne trade has expanded by nearly 3,000%, from under 0.5 billion tonnes in 1950 to nearly 12 billion tonnes annually today.

Text:

Annika Wall

Research Communications Officer

Department of Marine Sciences

Email: annika.wall@gu.se