School and student health

Valdemar Landgren discusses the increase in health problems among Swedish schoolchildren and suggests how we should think.

[Published 16 November 2023 by Valdemar Landgren]

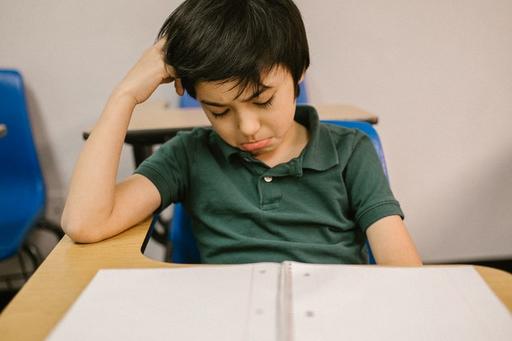

How does it show on you if you are not happy in your job? Aches, anxiety, and sleep difficulties can be physical signals that something is not right. Perhaps you can't keep up with the tasks expected of you. After a day at work, you feel completely exhausted. Maybe the thought of going to work begins to evoke discomfort. If you are fortunate, you can take control of your situation and, if necessary, seek another job. You can also simply resign.

But how would it feel if it were decided that you must work another nine years before the possibility of "resigning" could even be considered? Despite persistent discomfort, pain, sleep difficulties, and fatigue in the face of tasks you find overwhelming, you still have to keep working. This is the situation for many schoolchildren. Some eventually become "homebodies."

Health surveys aimed at schoolchildren have shown a noticeable increase in dissatisfaction, sadness, anxiety and sleep difficulties, especially in the past decade. At the same time, the number of referrals to Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Care (BUP) and paediatric medicine has steadily increased during the same period. What is the reason for this, and what is the actual state of students' health in today's Sweden? We tried to shed light on this in a recently published study (1).

It's not that there is a lack of research on children's health. The problem is that most research is done in isolation from each other, in different "silos." Someone investigates the development of school grades, some collect health surveys from children, others study specific conditions like asthma and obesity, and still others examine social factors or neuropsychiatric conditions. But for the individual, it is uninteresting to make these distinctions; for the individual, all these areas are part of a whole. They need to be understood together. Therefore, our approach was to use multiple perspectives simultaneously when undertaking the student health study.

The children were examined by doctors and psychologists in school. We reviewed medical records, collected forms from parents and also accessed results from national tests in grade 3. What was distinctive about the study was that for each participant, we weighed the information together and expressed the degree of clinical, i.e. significant ESSENCE problems (2)(referred to as neuropsychiatric/developmental neurological problems in the article; NDPs), whether they justified a diagnosis or not.

What did we find?

-

School difficulties, symptoms of stress, medical conditions, and neuropsychiatric problems were very common.

-

Children's health problems are complex, especially in those with school difficulties. More than half of those who failed national exams had either a medical diagnosis, pain, anxiety, or neuropsychiatric problems – often a combination of them. On average, this affected about 5 children per class.

-

Neuropsychiatric problems were common (40%) and had a clear connection to the results of national exams.

-

There is a greater chance of meeting the school doctor if you have foot pain than if you have school difficulties and neuropsychiatric problems.

Wrong person for the job

In Sweden, we have the peculiarity that principals are ultimately responsible for student health. The responsibility to create a plan for how to address this long list of health problems in schools falls on a person without medical training. In times of budget cuts and competition for students, schools need to save money. In such times, student health is rarely a priority. There is no healthcare institution that does the work we did in the study. The healthcare solution is a game of "patient ping-pong," where student health services, the medical centre, paediatric medicine, and Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Services (BUP) only see their "part" of the responsibility. In the middle is the family, bouncing back and forth between healthcare providers. This leads to a fragmented, inefficient, and prolonged healthcare process.

The school needs a workplace inspection

If worry, pain, and sleep difficulties were so common in a workplace, the union would have spoken up and turned to the labour inspectorate. But when it comes to schools, and the children are the employees, the situation is allowed to persist. Gillberg and Fernell, among others, have clearly shown how the Swedish National Agency for Education's curriculum is likely a driving factor in the situation. The curriculum demands independent work and abstract thinking, even though a large proportion of children have not developed these abilities, leading the curriculum to instead "disqualify" them. This hypothesis aligns well with our interpretation of the study's results and previous experience in the research group. The proportion with noticeable neuropsychiatric problems was around 10%, consistent with similar studies conducted in the 90s (3).

Today's school environment becomes a source of stress, and more of those with milder signs of, for example, concentration difficulties now experience "clinical problems" that lead to contact with healthcare. The attempt is to adapt children to reach the curriculum's goals instead of adapting the curriculum to how children actually function!

Paediatric Care on Mars

If humanity were to one day populate Mars, what do you think childcare would look like there? - Nothing would be ready from the start; it would need to be built from the ground up. The right to education and schooling for children is the starting point. I am quite certain that I would not wish for a healthcare system like the one in Sweden today. I would wish for paediatric care that is easily accessible in the child's everyday life. Children live in a small context centered around family and school – that is where medical and social support and concurrent ESSENCE competence should be. We really shouldn't have to move to Mars to realise that.

References

(1) Landgren, V., Svensson, L., Törnhage, C. J., Theodosious, M., Gillberg, C., Johnson, M., Knez, R., & Landgren, M. (2023). Neurodevelopmental problems, general health and academic achievements in a school-based cohort of 11-year-old Swedish children. Acta paediatrica (Oslo, Norway : 1992), Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.16989

(2) ESSENCE (Early Symptomatic Syndromes Eliciting Neurodevelopmental Clinical Examinations) is a collective term for all conditions involving early-onset behavioural problems and/or cognitive difficulties that lead to consultations with a variety of specialists, often without close collaboration among them.

(3) Thesis Neurodevelopmental disorders (ESSENCE): Early detection and outcome in adulthood

[This is a blog. The purpose of the blog is to provide information and raise awareness concerning important issues. All views and opinions expressed are those of the writer and not necessarily shared by the GNC.]