Photonic properties of diatoms

Short description

Diatoms are unicellular microscopic algae with cell walls (frustules) made of silica. The frustules have micro- and nanopores arranged in species-specific patterns through which exchange with the environment takes place (nutrients, gases, water, etc.). The underlying theory is that the photonic properties of diatoms are species-specific and based on different morphological characteristics as well as the light conditions they have been exposed to evolutionarily. Through advanced optical measurements, we investigate how different types of frustule pore geometries interact with light of various wavelengths.

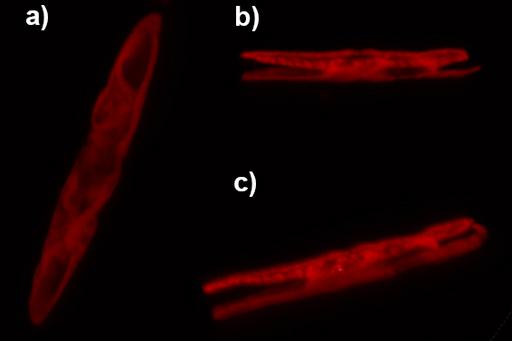

Diatoms, also known as diatomées, are unicellular microscopic algae with cell walls made of silica and a small amount of water. The cell consists of two halves, like a box with a lid. In the silica wall—the “shell” known as the frustule—there are tiny pores (ranging from micrometers to nanometers in size) arranged in a pattern specific to each species. These patterns are highly sculptural, and diatoms can rightly be called the jewels of the sea. Through these pores, the diatom exchanges substances with its surroundings, such as taking up nutrients and releasing waste products. The frustule also functions as mechanical protection and as a filter.

There are said to be anywhere from 20,000 to 2 million species of diatoms, and new species are continuously being discovered. The size of diatoms varies from a few micrometers to half a millimeter. Fossil evidence indicates that diatoms have existed for about 200 million years. They are divided into two major groups based on morphology: the centric diatoms, which are evolutionarily older and primarily found in open water, and the pennate diatoms, which diverged from the centric lineage about 90 million years ago and dominate benthic ecosystems as well as sea ice habitats.

It has been shown that the micro- and nanopores of the frustules interact efficiently with light, mainly through various diffraction processes (light-bending properties) that concentrate visible light into very small so-called "hotspots." Furthermore, as a result of the nanoporous patterns within the silica matrix, diatoms have been observed to exhibit photoluminescence — that is, they re-emit light at a wavelength different from the one they were illuminated with.

Thus, the frustules, with their complex pore patterns designed through millions of years of evolution, may serve not only as mechanical protection or filters against the surrounding environment but also as highly effective light collectors (funnels). This could help explain the diatoms’ highly efficient photosynthesis in both weak and strong light.

As for harmful ultraviolet light, it appears that the frustules may act as a kind of sunscreen, through several different processes that this project aims to identify and study in detail. This could help explain why diatoms, unlike many other groups of microalgae, seem to be tolerant of UV radiation, even though they generally lack UV-absorbing substances (such as pigments analogous to melanin in human skin).

This project is a collaboration between researchers from different disciplines, primarily within biology, physics, and engineering. The underlying theory is that the photonic properties of diatoms are species-specific and based on their various morphological characteristics as well as the light conditions they have been exposed to over evolutionary time. We predict a general difference between the oldest centric groups and the evolutionarily younger pennate groups. In particular, we expect this difference to be evident when frustules and intact cells are exposed to the ultraviolet parts of sunlight.

We study different types of frustules and, through advanced optical measurements, investigate how pore geometry functions as a light collector, light splitter, and light shield. Through biological experiments, we also expose selected species to increased intensities of UV radiation, and by combining ecophysiological and growth measurements, we compare species of different origins and morphologies, relating these traits to the potential UV protection provided by the frustule’s pore geometry.

Broadly speaking, all photonic properties found in the frustules of diatoms — in relation to ultraviolet, visible, and infrared light — can potentially be applied in various technological contexts, such as micro- and nanosensors in optochemical and biosensing systems, as well as in nanolenses and UV-protective materials or applications. A current area of interest is improving the efficiency of solar cells, with tests presently being conducted in Sweden and both within and outside Europe.